Why How We Meet Human Needs Matters More Than How Much We Spend

Every conversation about Universal Basic Income hits the same wall: “How do we pay for it?”

Wrong question. Here’s the right one: “Will giving people cash actually help them, or just make their landlords richer?”

I don’t support UBI. Not because we can’t afford it: we can. Not because I oppose helping people; quite the opposite. I oppose UBI because cash transfers into broken markets get captured by rent-seekers before they help anyone.

Give everyone $1,000 monthly and landlords raise rent $1,000. The purchasing power vanishes. The inequality remains. We’ve subsidized property owners with public money while pretending it’s progressive policy.

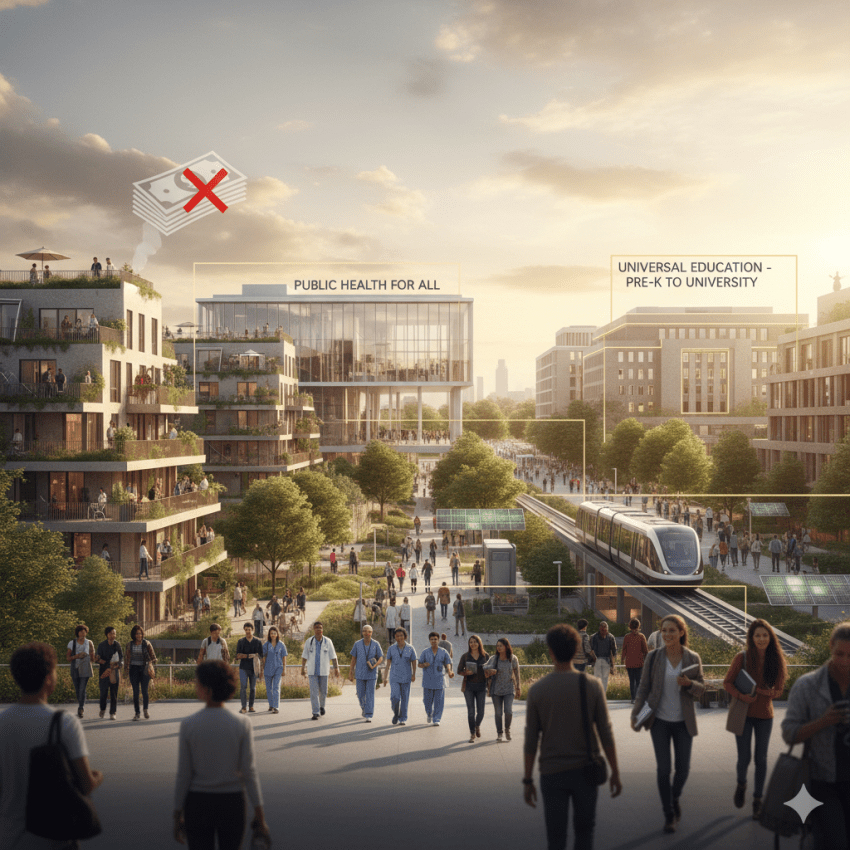

This is why the United States needs Universal Basic Assets: providing what people need directly (housing, healthcare, education) and removing these necessities from extractive markets entirely.

But this isn’t about choosing between capitalism and socialism. As I explore in “Beyond Capitalism vs. Socialism,” that’s a false choice that constrains our imagination. For seventy years, American political discourse has been trapped in a binary from the 1950s Cold War: free markets versus government control, individual liberty versus collective welfare.

Meanwhile, successful economies worldwide have abandoned this ideological purity for pragmatism. Singapore combines state capitalism with private enterprise. Nordic countries blend comprehensive welfare states with competitive markets. Germany merges worker representation with industrial leadership. These nations don’t debate capitalism versus socialism, they build what works for their cultures and contexts.

The real question isn’t which ideology to choose. It’s how do we use our understanding of monetary systems to build institutions that serve everyone in a pluralistic, diverse society? How do we create an economy where someone can choose a quiet, subsistence-level life without stigma, while their neighbor pursues wealth-building in competitive markets. Both can have dignity, security, and genuine opportunity?

Universal Basic Assets provides that framework. But first, we need to understand what actually constrains government spending.

Part I: There Is No Spending Constraint

Before comparing UBI and UBA honestly, align on one fundamental reality: the federal government has no spending constraint.

The federal government doesn’t “get money” from anywhere. When Congress authorizes spending, the Treasury instructs the Fed to credit bank accounts. Money is created by keystrokes. No vault. No pile of tax dollars. No Chinese credit card.

This isn’t political spin, it’s operational reality. Ask Fed officials, Treasury officials, or banking system operators. The government spends first (creating money), then taxes later (destroying money). Taxation doesn’t fund spending. It removes money from the economy to control inflation and redistribute purchasing power.

Still thinking “but where does the government GET the money?” You’re using the wrong mental model (you can find more detail about models in my essay, Why Economic Models Matter). The government creates currency. That’s what it means to be a currency issuer rather than a currency user.

This doesn’t mean unlimited spending is wise. Real constraints exist but they’re not financial. Understanding this difference changes everything.

Part II: The Real Constraint Is Inflation (Resources, Not Money)

Can the government create infinite money? Yes, operationally.

Should it? No, because real resources and productive capacity are finite.

As I discuss in “Beyond Capitalism vs. Socialism,” the constraint isn’t “running out of money.” The constraint is inflation. When you try buying more real stuff than the economy can produce.

Inflation happens when demand for real goods and services exceeds the economy’s capacity to produce them. That’s it. It’s a real resource constraint, not a money constraint.

Think about it: if the government spent $10 trillion building a bridge to Mars requiring materials that don’t exist and workers who aren’t available, you’d get massive inflation because you’re commanding real resources that aren’t there. But if the government spent $10 trillion mobilizing unemployed workers and idle factories to build needed infrastructure? Different story entirely.

What Actually Causes Inflation

Here’s what creates inflationary pressure:

- Supply shocks (COVID breaking supply chains, OPEC restricting oil)

- Monopoly pricing power (four companies control 80% of beef processing and coordinate increases)

- Bottlenecks (semiconductor shortage, port congestion, labor shortages in sectors)

- Sometimes excess demand (rarer than believed and when it does happen we should ask: for what, from whom, why?)

Notice what’s NOT on this list: “the money supply.”

The Evidence

The “too much money chasing too few goods” story is mythology:

- Federal Reserve created $4 trillion in quantitative easing after 2008 → Inflation stayed below target for a decade

- Japan ran massive deficits for 30+ years → Still fighting deflation

- US increased money supply dramatically 2020-2021 → Inflation appeared when supply chains broke and energy spiked, not proportionally to money creation

What actually happened in 2021-2022:

- Supply chains broken globally (COVID shutdowns)

- Energy shock (Ukraine war)

- Corporate profit margins hit record highs (pricing power, not cost pressure)

- Demand shifted from services to goods (creating bottlenecks)

- Housing costs soared (corporate investors buying properties, not “too much money”)

These are real economy factors: production, distribution, and market power problems. Not “too much money.”

Understanding this difference changes every policy conversation, including UBI versus UBA.

Part III: Why Cash UBI Fails: The Rent-Seeking Capture Problem

Now that we’ve established the real constraints (resources and production capacity, not money), let’s examine why Universal Basic Income doesn’t work.

Here’s the fundamental problem: if everyone receives $1,000/month for basic living expenses, landlords know this and raise their rent accordingly. The purchasing power gets captured by rent-seekers.

Give everyone $1,000/month and landlords raise rent $1,000. Give everyone healthcare vouchers and insurance companies raise premiums. Give everyone education grants and universities raise tuition.

This isn’t hypothetical, we’ve watched it happen:

- Student loans → tuition exploded 180% (inflation-adjusted) between 1980-2020

- Housing vouchers → landlords capture approximately 50% through rent increases

- Medicare/Medicaid → healthcare costs rising faster than general inflation

- Childcare subsidies → providers raised prices 8-15% in states with universal pre-K

Why This Happens: Inelastic Markets

You’re transferring cash into markets with inelastic demand where:

- People MUST purchase the good/service (housing, healthcare, food, education)

- Supply is constrained or controlled by powerful interests

- Switching costs are high or alternatives don’t exist

- Information asymmetries favor sellers

In these markets, any purchasing power increase gets captured by price increases. You’re not increasing people’s real consumption, you’re inflating asset prices and enriching rentiers (people extracting wealth through ownership rather than production).

The practical term: your UBI just became a subsidy for landlords, hospital systems, and monopolies.

UBI Doesn’t Solve Poverty: It Subsidizes Rent-Seekers

Here’s the brutal reality: UBI in the current market structure doesn’t lift people out of poverty. It transfers public money to private rent-seekers while maintaining the same relative deprivation.

If everyone gets $1,000/month:

- Landlords capture it through higher rents

- Grocery chains capture it through higher food prices

- Healthcare systems capture it through higher premiums

- For-profit colleges capture it through higher tuition

You’ve increased money flowing through these sectors without increasing the real supply of housing, healthcare, education, or food. Prices rise to meet the new purchasing power, and everyone ends up in the same relative position, except now the numbers are bigger and asset-owners are richer.

Why Local UBI Makes It Even Worse

Some propose implementing UBI at local or state levels to avoid federal political gridlock. But as I detail in “Why Progressives Are Accidentally Helping Authoritarians Win,” this makes the capture problem worse. Local UBI programs face:

- Resource exhaustion – Cities can only sustain cash transfers while tax bases hold up. Economic downturns gut local revenues precisely when programs are most needed.

- Business flight – Local businesses facing increased labor costs (due to UBI reducing desperation) can relocate to jurisdictions without UBI, taking the tax base.

- Faster rent capture – Landlords in local UBI programs know exactly how much money entered the market and can coordinate price increases more easily.

- No alternatives – Without federal resources to build public housing or healthcare alongside cash transfers, people remain trapped in rent-seeking markets with zero exit options.

Cash transfers need either federal scale or must be paired with public asset provision. Otherwise, you’re creating expensive subsidies for asset-owners funded by fragile local tax bases.

Part IV: Beyond the Protestant Work Ethic: Meeting Diverse Human Needs

Before explaining Universal Basic Assets, we need to reject a pernicious assumption underlying most policy debates: the Protestant work ethic philosophy that everyone must work to deserve basic dignity.

I don’t subscribe to this outdated idea. It discriminates against those with less access to resources or personal endowments. It punishes victims. In our modern world where we’ve privatized everything into markets and dismantled informal support networks and communities, it leaves people hopeless, politically exploitable, and economically fragile, rendering them incapable of the very “bootstrapping” they’re told to do. You can’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps if you don’t have boots.

The Reality of Diverse Human Situations

Consider the actual diversity of human circumstances:

Some people live in geographies that simply don’t have private sector strength to support minimum living standards. Rural areas, declining industrial towns, isolated communities are all places that lack the economic base for everyone to “just get a job” that pays enough to survive. Telling people to move ignores family ties, community roots, care responsibilities, and the reality that someone must live in these places for them to exist at all.

Some people lack the skills and capabilities to sustain themselves even with training and therapy. Disabilities, chronic illness, cognitive limitations, severe trauma are some examples of why not everyone can be made “productive” by market standards, no matter how much job training or counseling we provide. This doesn’t make their lives less valuable or worthy of dignity.

Some people may elect to live a simple life at a subsistence level. Maybe they want to focus on art, community service, care work, spiritual development, or simply enjoy quiet existence without market competition. In a wealthy, productive society, why should this choice be unavailable or stigmatized?

These situations shouldn’t be stigmatized but reflect living in a diverse country. The question is: how do we ensure we can ethically, sustainably, and in a dignified manner enable these situations while maximizing opportunity for people to climb up and compete in markets if they want to build prosperity and wealth?

Dignified Subsistence as a Human Right

We should provide a dignified minimum subsistence life for those who can’t or won’t work. Not as charity. Not as temporary assistance until they “get back on their feet.” As a basic guarantee of human dignity in a society with abundant resources.

This isn’t radical, it’s pragmatic. The private sector creates more than enough surplus value to support this. America’s productivity has increased dramatically since the 1950s, yet wages have stagnated while corporate profits have soared. The surplus exists. The question is how we distribute it.

Providing economic security also gives labor genuine negotiating power. When people aren’t desperate, they can reject exploitative jobs, demand better conditions, and pursue education or retraining safely. This shifts surplus value back to ordinary people from capital, reversing decades of mechanisms that transferred wealth upward (I talk about this in my essay How Corporate-Friendly Accounting Rules Create a $30 Trillion Transfer from Consumers into Wealthy Pockets).

What shifted surplus value from labor to capital since the 1950s:

- Declining union membership (from 35% to 10% of workforce)

- Weakened labor laws and enforcement

- Financialization rewarding shareholders over workers

- Tax policy favoring capital gains over wages

- Offshoring and automation threats suppressing wage demands

- Elimination of defined-benefit pensions

- Rising healthcare costs tied to employment (trapping workers)

Economic security through Universal Basic Assets reverses these dynamics. When survival isn’t at stake, labor has power.

Safety Nets for Ordinary People

Beyond subsistence for those who can’t or won’t work, ordinary people should have safety nets enabling bargaining power and opportunities:

Unemployment insurance that actually replaces income adequately and lasts long enough for genuine retraining or career transition: not the current system that barely covers expenses and runs out in months.

Supplemental basic income for workers in transition, care providers, students, artists, entrepreneurs building businesses, or anyone pursuing valuable work that markets don’t immediately reward.

Retraining and education support that covers living expenses while learning new skills, so people can adapt to changing economies without falling into poverty during transitions.

The point isn’t to eliminate work or market competition. It’s to ensure that participation in markets is genuinely voluntary and empowered rather than coerced by desperation. This makes both markets and democracy function better.

Part V: What Universal Basic Assets Actually Is

Universal Basic Assets solves the capture problem by removing necessities from rent-seeking markets entirely.

Instead of giving people money to buy housing in broken markets, provide public housing directly. Instead of vouchers for overpriced healthcare, provide healthcare free at point of service. Instead of student loans that inflate tuition, provide free public education.

You can’t price-gouge what’s provided publicly at cost.

What Are Universal Basic Assets?

UBA means guaranteeing access to essential resources through public provision:

Housing: Public housing… not segregated poverty concentration, but high-quality, mixed-income housing available to all. Vienna houses 62% of residents in social housing while maintaining one of Europe’s highest living standards. Singapore provides public housing to 80% of citizens. When I lived in White Plains, New York, I saw this model work in America: well-designed, mixed-income developments that integrated residents into the community and provided genuine pathways to opportunity. Germany’s extensive social housing demonstrates this approach at scale.

Healthcare: Single-payer, free at point of service. Nobody can charge you $1,000 for insulin if the public system provides it. Remove healthcare from profit extraction entirely.

Education: Free public education from pre-K through university, including trade schools and technical training. Remove education debt and barriers to advancement.

Transportation: Free or nominal-cost public transit. Remove transportation as a poverty trap.

Utilities: Public broadband, electricity, water at cost or free. Remove utility profiteering from natural monopolies.

Food Security: Expanded SNAP, universal school meals, community food programs. Ensure baseline nutrition outside grocery market dynamics.

Why Quality Implementation Matters

A critical objection: won’t public housing become slums? Won’t public services be terrible?

This is an implementation choice, not an inherent flaw.

In the past, U.S. public housing was often designed almost as segregated imprisonment of poor people. It wasn’t designed to integrate people into society and give them opportunities to build networks and rise into opportunity if they chose. This was a deliberate policy failure, not proof that public housing can’t work.

The contrast is stark:

Vienna’s social housing is so attractive that middle-class and even wealthy residents choose it. High-quality architecture, excellent maintenance, integrated amenities, mixed-income developments. It’s not “housing for the poor,” it’s community housing available to all.

Singapore’s HDB flats house 80% of the population in well-maintained, integrated developments with parks, markets, and community centers. Mixed-income by design. Pride of ownership through long-term leases. Maintenance funded from rents set at cost-recovery levels.

Germany’s social housing demonstrates this at scale across hundreds of cities. Quality construction, ongoing maintenance, integrated into neighborhoods, available across income levels with sliding rents.

White Plains, New York showed me this model can work in America. The mixed-income developments I saw there integrated residents into the broader community, provided quality housing without stigma, and created genuine opportunities for people to build networks and pursue advancement if they chose.

The lesson: Public provision doesn’t have to fail and become slums and overused. That’s an implementation choice. When we design UBA properly, high quality, mixed-income, integrated, well-maintained housing works.

UBA Creates the Foundation for Everything Else

Here’s what changes when your basic needs are met through public provision:

- You can take risks – Start a business, change careers, leave an abusive relationship, because you won’t lose housing or healthcare

- Labor markets rebalance – Employers can’t exploit workers with threats of homelessness and healthcare loss

- Entrepreneurship flourishes – As I detail in “Opportunity Economics,” when survival isn’t at stake, people can pursue innovation

- Education becomes about learning – Not about maximizing income to pay off debt

- Health improves – Preventive care, mental health, chronic condition management all become accessible

- Democracy strengthens – As I explore in “The Politics of Stakeholder Society,” people with secure foundations can engage civically rather than just surviving. When everyone has genuine economic security, they become full stakeholders in democratic society rather than being politically exploitable through economic desperation.

And here’s the kicker: Now cash UBI on top might actually work.

When your basic needs are met through public provision, cash supplements become discretionary income that actually increases consumption choices rather than just getting captured by rent-seekers. That $1,000/month isn’t going straight to your landlord, it’s actual purchasing power you can use.

Part VI: The “Soft-Money” Framework: Why UBA Makes More Economic Sense

Both UBI and UBA are “affordable”: we know the government can create the money for either. But they have very different effects on the real economy:

UBI’s Effect: Inflationary by Design

Cash UBI increases aggregate demand immediately:

- Everyone has more money to spend

- Demand surges across all sectors

- If the economy has slack (unemployment, idle capacity), this might boost production

- If the economy is near capacity, this creates inflationary pressure

- In rent-seeking sectors with inelastic supply, this just inflates prices

UBI is inflationary by design when there’s no corresponding increase in productive capacity. You’re increasing purchasing power without increasing real goods and services available.

UBA’s Effect: Building Capacity

Universal Basic Assets works differently:

- Builds productive capacity while distributing it – Public housing construction employs workers, creates housing stock, reduces homelessness, and removes housing from speculation

- Potentially anti-inflationary – UBA increases productive capacity (more housing, more healthcare capacity, more education) while meeting demand

- Stabilizes prices – Public provision of necessities at cost creates a price ceiling in those markets

- Mobilizes idle resources – Unemployed construction workers building housing, idle factories producing materials for infrastructure

- Addresses wealth inequality, not just income – UBA distributes productive assets, not just cash flows

The Job Guarantee Alternative

There’s another strategy that works within this framework: the Job Guarantee (JG).

A Job Guarantee means the federal government offers a job at a living wage to anyone who wants one. It functions as:

- An automatic stabilizer – Hiring expands when private sector contracts, shrinks when private sector expands

- A wage floor – Private employers must compete with JG wages and benefits

- A skills builder – Jobs include training and development

- Community focused – Local projects addressing community needs

The Job Guarantee addresses income security while building productive capacity (infrastructure, care work, environmental restoration, public services). It’s compatible with UBA. In fact, JG workers could build public housing, staff public clinics, teach in public schools.

The key commonality: Both UBA and JG organize real resources for public benefit rather than just transferring cash into broken markets.

Part VII: The Freedom Objection: Why Public Provision Expands Choice

“Public provision removes choice. People should decide what they want.”

Let me be clear: Freedom to choose between dying and going bankrupt isn’t freedom. It’s coercion.

The current system doesn’t offer real choice:

- You “choose” your health insurance (from whatever your employer offers, or bankruptcy)

- You “choose” your housing (from whatever you can afford, or homelessness)

- You “choose” your education (from whatever won’t drown you in debt, or economic immobility)

These aren’t choices. These are poverty traps dressed up as free markets. As I argue in “The Politics of Stakeholder Society,” this reflects a fundamental divide in how we think about who deserves to be a full stakeholder in American society… with real choice and real power, not just survival options.

UBA Expands Real Freedom

Universal Basic Assets actually expands choice:

- More career freedom – Take a job you love that doesn’t pay well, because survival is guaranteed

- More geographic freedom – Move for opportunities without worrying about losing healthcare or finding affordable housing

- More entrepreneurial freedom – Start that business without risking your family’s survival. As I argue in “Opportunity Economics,” economic security isn’t the enemy of opportunity… it’s the foundation that makes real opportunity possible.

- More educational freedom – Study what interests you, not just what maximizes income for debt repayment

- More relationship freedom – Leave bad relationships without facing homelessness

- More life freedom – Choose a simple, subsistence-level existence without stigma if that’s what brings you meaning and contentment

And here’s the important part: Public provision doesn’t eliminate private markets. You can still buy private housing if you want. Private insurance if you prefer. Private schools if you choose. Public provision creates a floor, not a ceiling.

Vienna has excellent public housing and people still buy private homes. Britain has NHS and people still buy private insurance. The difference is you’re not coerced by desperation into whatever exploitative arrangement rentiers offer.

Part VIII: Implementation: How Do We Actually Do This?

The good news: we already know how. We’ve done this before. Other countries are doing it now.

A Flexible, Multi-Level Approach

Universal Basic Assets can be implemented at federal, state, or local levels. You don’t need to wait for perfect alignment.

But here’s crucial context: While UBA can be implemented locally, it works best connected to national financial resources. As I explore in “Why Progressives Are Accidentally Helping Authoritarians Win,” purely local solutions face hard constraints. A community can only support as many public assets as local economic activity sustains. Without connection to national resource systems, local initiatives remain fragile and vulnerable to downturns.

This is why the most successful implementations combine local control with federal resources: communities decide what they need and how to implement it, but they aren’t artificially limited to local tax bases. Federal funding enables ambitious local programs that would be impossible with purely local resources. Think of it as national funding, local implementation: the best of both approaches. This is not new, it has been done for decades in the U.S. through Federal block-grant programs.

Federal implementation provides the most comprehensive approach with the greatest resources. As the currency issuer, the federal government can mobilize resources at scale without financial constraints, funding national programs like Medicare for All, universal public housing construction, or free public universities.

State-level implementation allows for experimentation and regional adaptation. States can create their own public option healthcare systems (as some are exploring), fund state university systems, build public housing, or provide universal pre-K. While states are currency users (unlike the federal government), they still have significant capacity, especially with federal support.

Local implementation enables communities to start immediately with programs tailored to local needs and values. Cities and counties can create municipal broadband, expand public transportation, build community housing, establish public banks, or provide universal school meals. Local action proves concepts and builds political support for broader implementation.

The key insight: you don’t need to wait for all three levels to act. Cities can start now. States can build on local successes. Federal programs can scale what works. This multi-level approach means UBA isn’t an all-or-nothing proposition: it’s a flexible framework that can begin wherever political will exists and expand as people experience the benefits.

Examples Across Levels

Housing:

- Federal: Direct funding for public housing construction nationwide, national standards

- State: State housing authorities building public housing, zoning reform enabling higher density

- Local: Municipal housing authorities (many cities already have these), community land trusts, inclusionary zoning. Cities like Vienna and the developments I saw in White Plains, NY show this works.

Healthcare:

- Federal: Medicare for All covering all services

- State: State public option healthcare (several states exploring this)

- Local: Municipal clinics providing free primary care, county hospitals expanding services

Education:

- Federal: Free public universities and trade schools, cancel existing student debt

- State: Free state university systems (already done in some countries for state residents)

- Local: Universal pre-K (many cities already provide this), expanded after-school programs

Transportation:

- Federal: Funding for state/local transit systems, high-speed rail between cities

- State: State transit authorities, regional rail systems

- Local: Free or low-cost municipal transit (Kansas City offers free buses), expanded bus and light rail

Utilities:

- Federal: National broadband infrastructure investment, regulation of natural monopolies

- State: State utility authorities, public power companies (many states already have these)

- Local: Municipal broadband (Chattanooga, TN: gigabit internet for $60/month), city-owned utilities (over 2,000 US cities already have municipal utilities)

Food Security:

- Federal: Expanded SNAP covering all food costs for low-income households

- State: State food assistance programs, farm-to-school programs

- Local: Universal school meals (already exists in some cities), community kitchens, farmers market subsidies

The Power of Multi-Level Implementation

Change doesn’t require waiting for perfect federal alignment. Cities can start now. States can build comprehensive systems within years. Federal programs can scale proven models nationwide. The winning formula: local control + federal resources = enabling ambitious programs that transcend local economic constraints.

Start wherever you can influence. Cities like Vienna (housing), Chattanooga (broadband), Kansas City (transit), and the developments in White Plains, NY prove local action works. States can experiment and adapt. Local success builds political support for state expansion. State victories create momentum for federal programs, which provide the resources to transform fragile experiments into robust alternatives.

This multi-level approach addresses conservative concerns about federal overreach. Communities implement UBA according to their values and circumstances. Rural areas prioritize different assets than cities. Conservative states structure programs differently than progressive ones. The framework is flexible while maintaining the core principle: everyone deserves access to basic assets for genuine opportunity.

As I discuss in “Opportunity Economics,” this federalist approach strengthens both democracy and markets through experimentation, jurisdictional competition, and local adaptation. And as I argue in “Why Progressives Are Accidentally Helping Authoritarians Win,” connecting local implementation to national resources transforms fragile experiments into resilient alternatives to corporate control.

Part IX: The Politics: Why Hasn’t This Happened?

If we have the real resources and the capacity to create the money, why haven’t we built Universal Basic Assets?

Politics. Power. Ideology.

- Rentier interests oppose it – Landlords, insurance companies, hospital systems, pharmaceutical companies, student loan servicers all profit from the current system. They lobby hard to maintain it.

- Deficit mythology – The pervasive belief that government debt is like household debt keeps people thinking we “can’t afford” things we absolutely can do.

- Fear of socialism – Public provision gets labeled “socialist” and associated with authoritarianism, even though many democracies provide these things.

- Just-world fallacy and Protestant work ethic – The belief that people must work to deserve basic dignity, that those who can’t or won’t work don’t deserve support. As I explore in “The Politics of Stakeholder Society,” this reflects conditional stakeholding the idea that stakeholder status must be earned through meeting specific criteria rather than being guaranteed based on humanity and presence in the community.

- Racial and class divisions – Opposition to universal programs often coded in racial terms (“welfare,” “inner-city,” etc.)

- Market fundamentalism – The ideological commitment to markets as not just useful but sacred, even where they demonstrably fail.

The question isn’t economic, it’s political. Do we want an economy organized around human flourishing or around extracting maximum profit from human needs?

As I outline in “Opportunity Economics,” building a coalition to overcome these obstacles requires moving beyond failed left-right divisions to unite people around policies that create genuine economic opportunities for everyone.

Conclusion: Beyond False Choices

Universal Basic Income asks: “How much cash do people need to survive?”

Universal Basic Assets asks: “What do people need to thrive, and how do we provide it?”

The difference isn’t semantic. The difference is structural.

- UBI treats poverty as a cash shortage. UBA treats it as lack of access to essential resources.

- UBI tries to patch a broken system. UBA rebuilds it.

- UBI gives people money to participate in extractive markets. UBA removes necessities from extractive markets entirely.

The evidence is clear:

- Financially, both are affordable, money isn’t the constraint

- Economically, UBI is inflationary (increases demand without capacity); UBA can be anti-inflationary (builds capacity while meeting demand)

- Empirically, UBI gets captured by rent-seekers; UBA escapes capture through public provision

- Socially, UBI maintains inequality with bigger numbers; UBA addresses wealth distribution directly

- Practically, UBI creates coercion with higher prices; UBA creates real freedom

As I explore in “Beyond Capitalism vs. Socialism,” the choice isn’t about capitalism versus socialism, markets versus government, or individual versus collective. These are false binaries that constrain our imagination.

The real choice is how we use our understanding of monetary systems to build institutions that serve a pluralistic, diverse society where anyone can choose quiet subsistence without stigma while their neighbor pursues wealth-building, personal power, presetige- whatever their motivation is for being in the markets… both lifestyles have dignity, security, and genuine opportunity.

Markets excel at many things. But rationing human survival and dignity by ability to pay isn’t one of them. Some things are too important to leave to profit motives.

Universal Basic Assets provides the framework for this pluralistic vision:

- Those who can’t work get dignified subsistence

- Those who won’t work in traditional markets get basic security

- Those in geographies lacking private sector strength get genuine opportunities

- Those pursuing education, care work, art, community service, or entrepreneurship get real support

- Those competing in markets for wealth-building get fair conditions and genuine choice

- Everyone gets stakeholder status, democratic participation, and pathways to contribute

This isn’t charity or temporary assistance. It’s the foundation for a society that works for everyone using our abundant productive capacity to ensure everyone has what they need to live with dignity, while preserving and enhancing freedom for those who want to compete and build.

We have the resources. We have the capacity. We have the knowledge.

What we need, as I discuss in “Opportunity Economics,” is the political will to choose solidarity over extraction, long-term flourishing over short-term profit, and human dignity over market fundamentalism.

The best part? You don’t have to wait.

Universal Basic Assets can start at any level. Your city can provide universal broadband or free transit. Your state can create public healthcare options or free public universities. Local successes build pressure for state action. State victories create momentum for federal programs. Change begins wherever political will exists.

The question isn’t “Can we afford Universal Basic Assets?”

The question is: In a society with unprecedented productive capacity, how much longer will we tolerate organizing our economy around artificial scarcity and extractive markets when we could ensure everyone’s basic needs while maximizing genuine freedom and opportunity?

We’re not choosing between capitalism and socialism. We’re choosing what kind of capitalist democracy we want to be: one that rations survival by market power, or one that guarantees basic security while enabling genuine opportunity for all.

The framework is here. The resources exist. The only question is whether we have the political courage to build it.

Appendix A: The Mathematics: Why Mainstream Models Fail and What Actually Works

Note: This appendix provides formal economic analysis for readers interested in the mathematical case for UBA over UBI. The main essay stands independently without requiring this technical detail.

Mainstream economists who focus on “hard-money” theories dismiss “soft-money” solutions as theoretically unsound. Fair enough. Let’s use their own models instead.

Here’s the problem: mainstream predictions have failed spectacularly and repeatedly for decades. When models can’t predict reality, you question the models: not reality. Mainstream Economics simply does not have that kind of basic institutional introspection, which is why I argue that Economics is Not a Science.

Let’s examine three major failures, then show which models actually explain what we observe.

When Mainstream Models Predicted Disaster (And Got It Wrong)

Mainstream economic theory makes specific, testable predictions. When reality contradicts these predictions repeatedly, we should question the models not ignore the evidence.

Prediction 1: Quantitative Easing → Hyperinflation

The Quantity Theory of Money states: MV = PY

Where M = money supply, V = velocity, P = price level, Y = real output

This theory predicts that increasing M (money supply) with constant V and Y should proportionally increase P (inflation). When the Federal Reserve created $4 trillion through quantitative easing after 2008, mainstream economists predicted massive inflation.

What happened: Inflation stayed below the Fed’s 2% target for over a decade. The model failed.

Prediction 2: Large Deficits → Crowding Out

Mainstream “crowding out” theory predicts: G↑ → r↑ → I↓

(Government spending increases → interest rates rise → private investment falls)

Japan ran enormous fiscal deficits for 30+ years, sometimes exceeding 10% of GDP. Mainstream models predicted skyrocketing interest rates that would crowd out private investment.

What happened: Japanese interest rates stayed near zero or went negative. Private investment was constrained by lack of demand, not lack of available credit. The model failed.

Prediction 3: Low Unemployment → High Inflation (Phillips Curve)

The traditional Phillips Curve predicts: π = f(u) where inflation (π) is a decreasing function of unemployment (u).

Between 2015-2019, U.S. unemployment fell from 5.3% to 3.5% well below what mainstream economists considered the “natural rate.” They predicted accelerating inflation.

What happened: Inflation remained low and stable. The model failed.

The Pattern: Mainstream models consistently fail because they’re based on incorrect assumptions about how monetary systems work. They assume money is scarce, government spending crowds out private activity, and inflation is primarily monetary. Reality shows otherwise.

The Capacity Utilization Model: What Actually Drives Inflation

If mainstream models fail, what explains the data? A capacity-focused approach:

π = β(Y – Y)/Y**

Where:

- π = inflation rate

- Y = actual output (aggregate demand)

- Y* = potential output (productive capacity)

- β = sensitivity parameter (how quickly prices respond to demand pressure)

The key insight: Inflation occurs when demand (Y) exceeds capacity (Y*), creating an “output gap.” This explains all the empirical anomalies:

- QE didn’t cause inflation because the economy had massive slack (Y << Y*). More money didn’t increase Y enough to exceed Y*.

- Japanese deficits didn’t cause inflation because Japan had persistent excess capacity. Government spending increased Y but never exceeded Y*.

- Low unemployment didn’t cause inflation (2015-2019) because capacity had expanded better technology, higher productivity, more efficient supply chains increased Y*.

This model makes different predictions for UBI versus UBA:

UBI’s Inflationary Effect

Universal Basic Income increases aggregate demand without increasing productive capacity:

Initial state: Y₀ < Y*₀ (economy has some slack)

UBI implemented:

- Everyone receives income U

- Aggregate demand increases: Y₁ = Y₀ + (U × MPC)

- Where MPC = marginal propensity to consume

- Capacity unchanged: Y₁ = Y₀

Result: If (Y₀ + U×MPC) > Y*₀, then inflation increases: π₁ > π₀

Even if the economy has initial slack, UBI creates inflationary pressure as demand approaches or exceeds capacity. And this is the best case scenario where slack exists. In sectors with no slack (housing, healthcare), the effect is immediate.

UBA’s Capacity-Building Effect

Universal Basic Assets increases both demand AND capacity:

Initial state: Y₀ < Y*₀

UBA implemented:

- Government builds public housing → employs construction workers (↑Y) + increases housing stock (↑Y*)

- Government expands healthcare → employs medical workers (↑Y) + increases care capacity (↑Y*)

- Government funds education → employs teachers (↑Y) + increases skilled workforce (↑Y*)

Result: Y₁ = Y₀ + ΔUBA and Y₁ = Y₀ + ΔUBA

If capacity increases match or exceed demand increases, inflation remains stable or even decreases: π₁ ≤ π₀

This is why UBA can be anti-inflationary while UBI is inherently inflationary. UBA mobilizes unemployed resources to build productive capacity, while UBI just increases purchasing power chasing existing capacity.

The Rent Capture Problem: Price Elasticity in Essential Markets

Mainstream economists should understand this problem, after all, it’s their own theory of price elasticity.

Price elasticity of demand: ε = (ΔQ/Q)/(ΔP/P)

Where Q = quantity demanded, P = price.

- When ε > 1 (elastic): Consumers respond to price changes by significantly changing quantity purchased

- When ε < 1 (inelastic): Consumers cannot significantly change quantity even as prices rise

- When ε → 0 (perfectly inelastic): Consumers must purchase regardless of price

Essential goods have low elasticity:

- Housing: ε ≈ 0.3-0.5 (you need somewhere to live)

- Healthcare: ε ≈ 0.1-0.3 (you can’t decline treatment for life-threatening illness)

- Education: ε ≈ 0.3-0.5 (credentials required for economic mobility)

- Food: ε ≈ 0.5-0.8 (you must eat)

The UBI Capture Model

When cash transfers enter inelastic markets, suppliers capture the transfers through price increases:

Initial state:

- Equilibrium price: P₀

- Equilibrium quantity: Q₀

- Consumer income: I₀

UBI implemented: Everyone receives U

New equilibrium:

- Consumer income: I₁ = I₀ + U

- Price increases: P₁ = P₀ + αU

- Where α = capture coefficient (0 ≤ α ≤ 1)

For inelastic goods (ε → 0):

- Quantity barely changes: Q₁ ≈ Q₀

- Suppliers raise prices to capture income: α → 1

- Consumer real gain: U – αU → 0

The formula for rent capture:

Real purchasing power gain = (1 – α)U

In perfectly inelastic markets where suppliers have pricing power, α approaches 1, meaning consumers gain almost nothing in real terms.

Empirical Evidence of Capture

We’ve observed this capture mechanism repeatedly:

Student loans: Government increased loan availability → tuition rose to capture it

- Average tuition increased 180% (inflation-adjusted) between 1980-2020

- Loan availability: strong positive correlation with tuition increases

- Real education quality: minimal improvement

Housing vouchers (Section 8): Government provides housing assistance → rents rise in qualifying areas

- Studies show landlords raise rents by approximately 50% of voucher value

- α ≈ 0.5 for housing vouchers

Childcare subsidies: Government subsidizes childcare → providers raise prices

- States with universal pre-K saw private childcare prices rise 8-15%

- The subsidy gets partially captured by providers

UBA Escapes the Capture Problem

Public provision solves this mathematically by removing goods from price-setting markets:

Public housing provision:

- Rent set at cost-recovery: R = C/N (where C = total costs, N = number of units)

- No profit maximization: α = 0

- Real benefit to consumers: Full value of housing

Public healthcare:

- Price at point of service: P = 0

- Funded through progressive taxation

- No rent capture possible: α = 0

The general principle:

When goods are provided publicly at cost, the capture coefficient α equals zero, meaning consumers receive the full value rather than transferring wealth to rentiers.

Combining the Models: Why UBA Dominates UBI

Let’s combine capacity and elasticity models:

UBI scenario:

- Increases demand: Y↑

- Capacity unchanged: Y*→

- Inflationary pressure: π↑

- In inelastic markets: prices capture transfers (α → 1)

- Real benefit approaches zero in essential goods

UBA scenario:

- Increases demand: Y↑

- Increases capacity: Y*↑

- Inflationary pressure: π → or π↓

- Public provision: no rent capture (α = 0)

- Real benefit equals full value of assets provided

The Formal Comparison

Let’s compare total welfare effects:

UBI welfare gain:

W_UBI = Σᵢ(1 – αᵢ)Uᵢ – πU

Where:

- i indexes different goods (housing, healthcare, food, etc.)

- αᵢ = capture coefficient for good i (high for inelastic goods)

- Uᵢ = portion of UBI spent on good i

- π = inflation induced by aggregate demand increase

For highly inelastic essential goods where αᵢ → 1, welfare gain approaches zero or negative.

UBA welfare gain:

W_UBA = Σⱼ(Vⱼ) + ΔY – Costs*

Where:

- j indexes different public assets

- Vⱼ = value of public asset j to consumers

- ΔY* = increase in productive capacity (reduces future inflation)

- Costs = real resource costs of building assets (labor, materials)

Since public assets are provided at cost with no rent capture:

- Full value delivered: no α reduction

- Capacity expands: reduces inflation

- Future production enabled: increases Y* permanently

What This Means

The mathematics is unambiguous. UBA dominates UBI:

- UBI faces double erosion: Rent capture (α → 1) reduces nominal gains, then inflation (π) erodes what remains

- UBA escapes both: No rent capture (α = 0), plus capacity expansion (↑Y*) prevents inflation

This isn’t ideological preference. It’s what formal models predict when using frameworks that explain observed behavior rather than assuming frictionless markets and neutral money.

Mainstream economists already use these tools. They analyze capacity utilization (though they ignore it in policy prescriptions). They understand price elasticity (though they rarely apply it to welfare programs). The difference: capacity and elasticity models predict what we observe. Monetary models consistently fail.

The question isn’t whether government can create money for either program, we have already discussed the ansewr to that: they can. The question is which program delivers real benefits rather than transferring wealth to rentiers. The mathematics clearly favors UBA.

Appendix B: From Theory to Policy: Implementing the Capacity and Anti-Capture Framework

Note: This appendix translates the mathematical models from Appendix A into concrete policy design principles and implementation mechanisms.

Using the Capacity Utilization Model in Policy Design

The capacity model π = β(Y – Y)/Y** provides clear guidance for policy sequencing and scale:

Policy Principle 1: Measure Slack Before Scaling

Before expanding UBA programs, assess sector-specific capacity utilization:

- High unemployment in construction? → Scale public housing construction

- Idle healthcare facilities? → Expand public healthcare access

- Underutilized educational capacity? → Expand free public education

Implementation: Require quarterly capacity utilization reports before program expansion. When sector capacity < 80%, green-light expansion. When capacity > 90%, slow expansion and invest in building capacity first.

Policy Principle 2: Sequence for Capacity Building

Don’t just provide assets, build the productive infrastructure to sustain them:

Phase 1 (Years 1-3): Train workers and build initial facilities

- Expand medical school funding and residency programs

- Create apprenticeship programs for construction trades

- Fund teacher training and credential programs

Phase 2 (Years 3-7): Scale asset provision as capacity grows

- Open new public housing using newly trained construction workers

- Expand public clinics as new doctors complete training

- Add public university seats as new faculty are hired

Phase 3 (Years 7+): Maintain capacity growth ahead of demand

- Continuous training pipelines ensure capacity expansion outpaces demand

- Result: π remains stable or decreases (anti-inflationary)

Using the Rent Capture Model to Design Anti-Capture Policies

The capture coefficient α (where Real Gain = (1 – α)U) shows how to prevent rent-seeking:

Policy Principle 3: Public Provision Where α Is High

Target public provision at sectors with highest capture coefficients:

Priority 1 (α > 0.7): Full public provision

- Healthcare (ε ≈ 0.1-0.3, α → 0.9)

- Housing in tight markets (ε ≈ 0.3-0.5, α → 0.8)

- Higher education (ε ≈ 0.3-0.5, α → 0.7)

Priority 2 (0.4 < α < 0.7): Public option competing with private

- Transportation

- Utilities

- Childcare

Priority 3 (α < 0.4): Market provision with regulation

- Most consumer goods

- Discretionary services

Implementation: Annual studies measuring α by sector. When α exceeds 0.6 for essential goods, trigger policy review for public provision.

Policy Principle 4: Design to Minimize α

When implementing UBA programs, design to prevent capture:

For Public Housing:

- Set rents at cost-recovery only: R = C/N (zero profit margin)

- Mixed-income design: Prevent market segmentation that enables price discrimination

- Integrate geographically: Prevent isolated locations where private landlords can charge premiums

- Quality parity with market: Ensure public option competes on quality, preventing “prestige premium” capture

For Public Healthcare:

- Free at point of service: P = 0 (eliminate ability to charge)

- Negotiate drug prices centrally: Monopsony power prevents pharmaceutical α

- Prohibit balance billing: Prevent providers from charging above public rates

- Cover comprehensively: Gaps create opportunities for supplementary insurance capture

For Public Education:

- Zero tuition: Eliminate price mechanism entirely

- Cover living expenses: Prevent private student loan α capture

- Quality investment: Ensure public universities compete with private on outcomes

- Geographic coverage: Commuting-distance public options prevent relocation costs enabling α

Monitoring and Adjustment Mechanisms

Policy Principle 5: Build Feedback Loops

Create institutional mechanisms to measure and respond to capture attempts:

Quarterly Monitoring:

- Track private market prices in sectors with UBA provision

- Calculate effective α: (Private Price Increase)/(UBA Value) after program launch

- If α > 0.3 in adjacent markets, investigate and adjust policy

Example: Public Housing Launch

- Month 0: Launch public housing program in city

- Month 3: Measure private rental price changes in same area

- If private rents increased > 30% of public housing value → private landlords attempting capture through location premium

- Response: Accelerate public housing geographic coverage to eliminate location advantage

Annual Reviews:

- Measure Y/Y* by sector to ensure capacity growing ahead of demand

- Assess program quality to prevent degradation driving people back to private markets (which enables α)

- Survey beneficiaries about unmet needs indicating gaps where α could emerge

Concrete Policy Proposals Using This Framework

Example 1: Public Housing Implementation

Year 1-2: Build Capacity

- Fund 50,000 new construction apprenticeships

- Establish federal-local partnerships identifying sites

- Set design standards: mixed-income, integrated, high-quality

Year 3-5: Initial Provision (Low α Design)

- Build 500,000 units in 50 cities

- Rent = operating costs only (α = 0 by design)

- Geographic distribution prevents private landlord location premiums

- Quality standards prevent “luxury premium” capture

Year 6-10: Scale

- Add 1 million units annually

- Continuous capacity building keeps Y* > Y

- Monitor private rent changes; if increasing, accelerate public construction

Year 10+: Steady State

- 30-40% of housing stock public

- Private market cannot charge premiums (too much public competition)

- α maintained near zero through adequate public supply

Example 2: Medicare for All Implementation

Year 1: Capacity Assessment

- Measure current healthcare utilization vs. capacity

- Identify bottlenecks (primary care, specialists, facilities)

- Fund medical school expansion for 5-year pipeline

Year 2-3: Gradual Rollout (Preventing Capacity Constraints)

- Year 2: Cover all children and 55+ (highest need, known capacity)

- Year 3: Add 45-54 age group

- Monitor Y/Y* in healthcare: ensure capacity adequate before next expansion

Year 4: Full Coverage

- Universal coverage once capacity confirms Y* > projected Y

- α = 0 by design (free at point of service, no balance billing)

- Drug price negotiation eliminates pharmaceutical α

Ongoing:

- Continuous medical training pipeline

- Facility expansion funded as needed

- Quality monitoring prevents degradation that would push people to private supplementary insurance (preventing α emergence)

Key Implementation Principles Summary

- Measure before expanding: Know your Y/Y* to prevent inflation

- Build capacity first: Invest in training and facilities before demand

- Design for α = 0: Public provision at cost, no profit opportunities

- Monitor for capture: Track private market responses, adjust quickly

- Quality matters: Poor quality public provision creates opportunities for private α capture

- Geographic coverage: Gaps enable location-based rent-seeking

- Comprehensive coverage: Gaps enable supplementary market α

- Continuous capacity investment: Keep Y* growing ahead of Y

Political Economy Considerations

Transitional Policies to Reduce Opposition:

The models suggest phasing strategies that minimize disruption while preventing capture:

For housing:

- Don’t expropriate existing landlords

- Instead, build enough public housing that private landlords must compete on quality/price

- As public supply grows, private rents stabilize (reducing α naturally)

- Voluntary program reduces political opposition

For healthcare:

- Allow existing private insurance for non-covered services initially

- As public coverage expands and proves superior, private insurance market naturally shrinks

- Providers transition voluntarily as patient base shifts

- Less disruption than forced transition

The key insight from the models: You don’t need to eliminate private markets. You just need to build enough public capacity that α approaches zero because rent-seekers can’t charge premiums when high-quality public alternatives exist.

This transforms UBA from “government takeover” to “effective competition that forces private markets to actually serve consumers.”