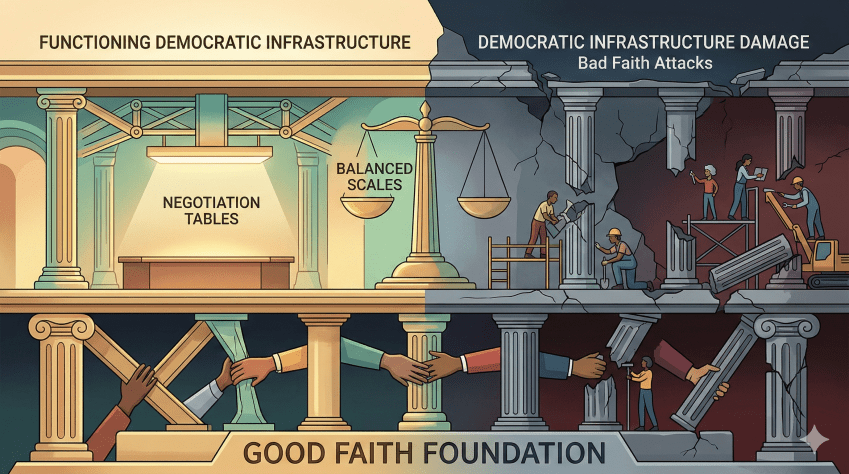

American democracy runs on infrastructure most people have never been taught about. Not the Constitution or elections—something more fundamental: the commitment that when Americans disagree, they negotiate in good faith.

Good faith means everyone’s interests get a seat at the table. It means the process of working things out together is what makes the country work. Human rights and inclusivity aren’t soft liberal values—they’re the operating infrastructure that makes democratic governance possible.

This essay examines what good faith governance actually is, the specific political strategies that broke it (the Southern Strategy, corporate economic mythology, Gingrich’s obstruction playbook, Trump’s authoritarian rhetoric, Bannon’s reality-breaking), and why everyone should care about defending it.

Key arguments:

• Good faith is American infrastructure – It’s not civility or “being nice.” It’s the mechanism that makes negotiation possible when interests conflict.

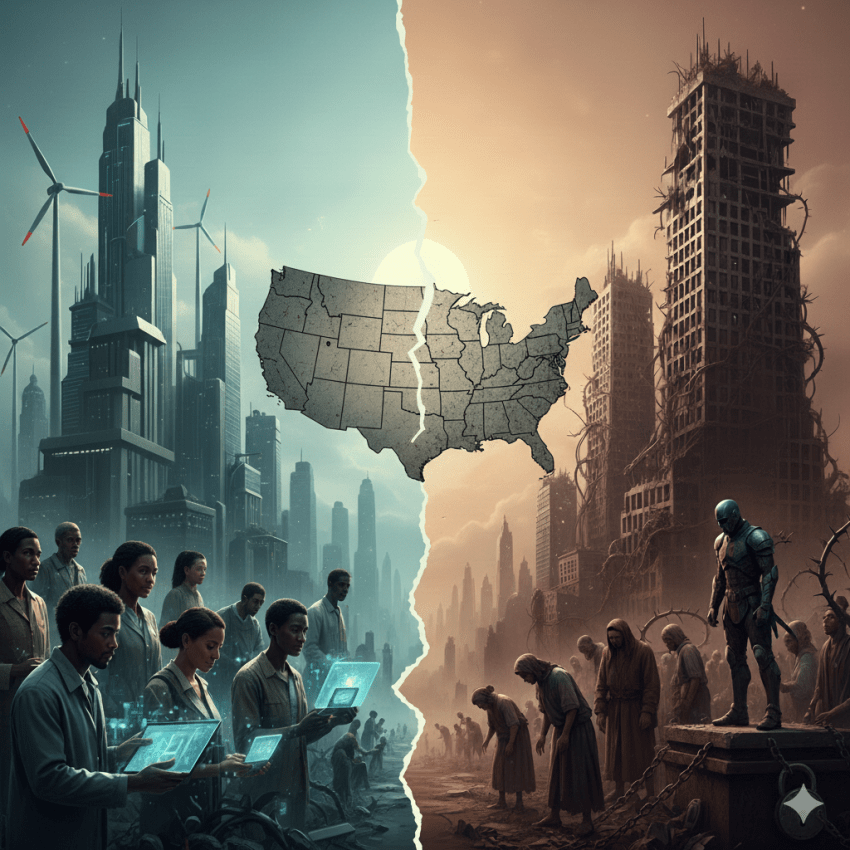

• Breaking good faith breaks democracy – Each political strategy identified involves denying the legitimacy of some group of Americans as democratic participants.

• This hurts everyone – When the system that protects everyone’s interests breaks, nobody is protected. Not the people who broke it, not the people they claim to represent.

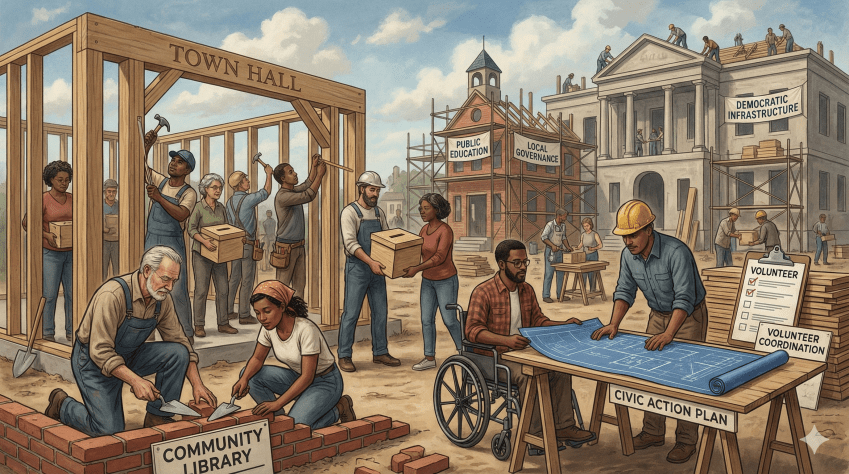

• The middle class was manufactured through good faith governance – The GI Bill, progressive taxation, union protections, public universities, Social Security—deliberate policies that built broadly shared prosperity.

• Fair competition requires active governance – Every period of American prosperity had government actively maintaining the playing field. When it stopped, wealth flowed upward.

• You have language to call this out – The essay provides specific phrases for specific conversational situations. Bad faith is un-American. You can say that.